|

LEWIS

CARROLL .CO.UK

|

|

|

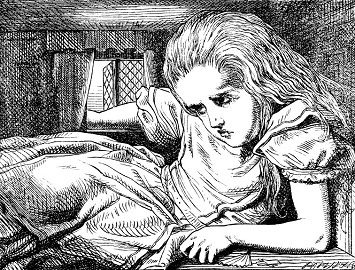

Alice's Adventures Under Ground Read by Chapter: I, II, III, IV You can also view it in the British Library web archives: here

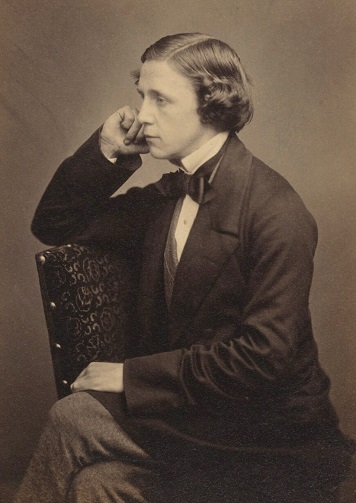

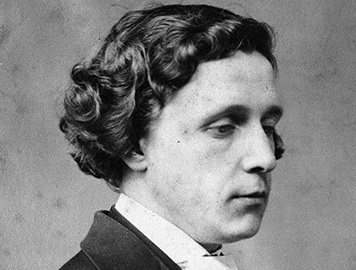

'Alice's Adventures Under Ground' was the first version of what was to become known as 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'. As we are all told, this story was inspired from a boat trip on 4th July 1862 - the so-called 'Golden Afternoon' - when Charles Dodgson, accompanied by the Rev. Robinson Duckworth, took the three Liddell children in a rowing boat from Folly Bridge in Oxford, 5 miles up the Isis river to the village of Godstow. It was not, in actual fact, a particularly 'golden' afternoon, the weather being cloudy, rainy, and cool. However, the memory of that trip, and the imagination and company of that day, seems to have remained golden in Dodgson's memory. In fact, Dodgson had taken Liddell children on several earlier similar trips, starting with Harry and his sister Lorina (Ina) several years before (1857 onwards). Furthermore, though we are told that on that day in 1862 Alice had encouraged Charles Dodgson to write down the story, the adventures of Alice 'in wonderland' actually unfolded over several afternoons. They would take picnics and Duckworth (who was also a renowned singer, who later served the Royal Family, and is referenced in the story as 'The Duck') would row, as Dodgson and the children made their own journeys of imagination, in their 'other world' away from the city, the formalities, and conventions of the adult world. In the summer of 1862 Ina was 13, Alice was 10, and Edith was 8 years old. In early August they went on another trip on the river, where Charles Dodgson explored the story further. Three months after that, in November 1862, he got fully to work on the manuscript. It would be two years later that Dodgson would give Alice the completed manuscript, with the dedication: 'A Christmas Gift to a Dear Child in Memory of a Summer's Day'. The narrative continued to evolve. In the hand-written manuscript he has not yet included the well-oknown passages involving the Cheshire Cat and the Hatter's Tea Party. These were part of a 12000 word expansion when the book was sent to Macmillan and Co for printed publication in 1865: see this page here for exploration of this printed version, 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'. Dodgson would publish a follow-up story, 'Through the Looking Glass', in 1871. That book is explored on this page here. It is tempting to read the 'Alice' stories as a simple and na´ve mixture of innocence, quirkiness and nonsense. However, analysis demonstrates that Dodgson embedded many references to contemporary themes in the stories, including allusions to mathematics, to chess, to politicians, to the critic John Ruskin (who taught the Liddell children painting), to Latin, to logic, and to people and places in Oxford. The stories are thread through with contemporary Victorian allusions, suggesting that Dodgson pitched the tales for adults as well as for children. There are hidden references and parodies, some probably lost over time. At the same time, many modern readers are fascinated by more metaphysical themes, and the concept of 'other worlds' implicit in either psychology or theoretical physics. The impression of more idyllic weather on that day in 1862 was expressed in a poem at the end of 'Alice Through the Looking Glass' - the one which people name after its opening line: 'A Boat Beneath a Sunny Sky'. It describes the end and coming evening of a sunny, dreamy day. In a sense this may be seen as a construct, a composite perhaps of various trips on the river, to communicate the sense of dreamy otherworldliness in which the Alice stories unfolded. But even if the poem does not descibe the actual weather on that first day when the stories began (and possibly a memory of a subsequent trip or an idealisation) it seems to communicate idyllic and eternal themes of the passage of time, and the 'own world'-ness of the present, and people we share with, from which we find ourselves cut off from. And yet in that 'other world' of the time itself, it is always happening, always resonating in the now. As Dodgson looked back, that sunny day of childhood innocence (and recall of his own childhood innocence may be enveloped too), seemed "cut off"... the "autumn frosts have slain July". The spell of that summer day (or several summer days) seemed almost to exist in its own country, open to some other world, or dimension, or imaginative realms: realms that were possible because of children's capacity to be "eager" and "willing" to open to them. And yet, at the later date when the poem was written to frame the adventures, to Dodgson time has already stolen those 'otherworld' moments away. The children, the golden hours... they too are now consigned to a wonderland, as if asleep and dreaming... "as the summers die". "In a Wonderland they lie." Time was ever flowing on and on like the river, carrying each person off, through the "autumn frosts" to the dead of winter. Life itself, our lives, our moments together... as time drifts on... become like dreams. And yet on that 'sunny day', even as childhood is so momentary and ephemeral, "ever drifting down the stream"... there is a happening, some sense of happening in the moment, a 'nowness'... and Dodgson's poem seems to lapse towards the numinous and mysterious. He sees the time of freed imagination, shared with the children, as in some way an opening of a reality, not a closing down: there seems at times like this to be a gleam on the surface of existence, and "lingering in the golden gleam" he appears to be communicating an 'other world' (maybe a deeper world) that is sometimes encountered, sometimes experienced in certain episodes in life. The children, their imagination, the simplicity of kindness and security as they "nestle near"... these things seem to make possible the tremulous belief. And the temporary suspension of disbelief. Years later Dodgson is still haunted - "still she haunts me" - though whether he is referencing Alice Liddell or the Alice of that under ground world, it is perhaps hard to be sure (and he may not have known himself). The sense of mortality, implicit in the ever flowing river is always there. In the Victorian times, with high infant mortality, death was always close by. Ina Liddell would be dead at the age of 22, before the 'Sunny Sky' poem was written. There is a strong sense in Carroll that life itself is so vulnerable, so temporary, that each one of us all too soon become part of 'other worlds' cut off from the world other people inherit, as if we are little more than dreams. Hence the reflection at the end of the poem that tries to express that boat journey together: "Life, what is it but a dream?" 'Alice's Adventures Under Ground' was Dodgson's gift in response to Alice Liddell's request that he write the story down. It was hand-written by Dodgson with 37 of his own illustrations, and is now in the care of the British Library, who have given me permission to reproduce it on this website. You can read and enjoy it here: Read by Chapter: I, II, III, IV You can also view it in the British Library web archives: In Spring 1863 Charles Dodgson sent an incomplete version of this manuscript for the children of his friend George MacDonald to read and they were enthusiastic. He took the unfinished manuscript to the publisher Macmillan and they liked it too. Finally, in November 1864, he presented the hand-written and illustrated manuscript to Alice Liddell. He had considered other possible titles including 'Alice Among the Fairies' and 'Alice's Golden Hour' but at this pointed he opted for 'Alice's Adventures Under Ground'. Although the print version of the story would become 'Alice's Adventures in Wonderland', a facsimile of the original hand-written 'Under Ground' manuscript would be produced in 1886. And so the imaginative openings on the river, involving 5 people, started reverberating out across the world, in the end to millions. * * * * * * * ~~~ REVERIE ~~~ My aunt and her daughter Menella lived deep in the Kent countryside, down a secluded woody lane, fringed with fields of hops. My cousin Menella had grown up there, playing in the expansive garden with its apple orchards, vegetable garden, flower beds, and lawns that seemed to stretch far away. It was its own secluded world. My first time in the garden was utterly beautiful, a day of blue skies, and the scent of flowers drifting on the gentlest summer breeze. 'Come and see the garden,' she said. So I went. It was one of those sun-filled 1950s summers that would surely go on forever. To a child it seemed that way. The garden was a dreamy place, and there were hidden corners to explore. Recollecting from this other world today it seemed like the sun-soaked days would never end. She led me out beyond the apple orchard, leaving the summerhouse behind, down the long lawn to the far, far end of the gardens... until the main house was hidden by the softly billowing trees, and all I could see was the chimney pots. There in seclusion we sat down, talking quietly, and lay back in the clover, gazing up at the blue heavens overhead, where occasional little white clouds sailed by, though the warmth of the sun never relented. 'Would you like me to tell you a story?' she said. 'It started in this garden.' 'Alright,' I replied. I liked her. She was much older than me but it didn't seem to matter. With her I felt safe and her friendliness was natural and matter of fact. She was straightforward and kind. Looking back over all these intervening years, I don't think I understood, as her quiet voice sauntered on, what she meant when she said 'strange things have happened in this garden': though I know it now, which isn't the same as saying I understand it all. If you are a receptive, encounters happen, but it's not like you go looking for them. It's not like they're all worked out and understood. They don't need to be. Those childhood days are now far off, another world from which I seem completely cut off and separated. And yet... they still seem present, somehow co-existent. Just, in another world. I didn't know at the time that I would live there - you never know at the time what lies ahead - but when Menella's ageing mother decided to move to somewhere with less maintenance, she passed the house and the beautiful garden to my parents, and so I spent my early childhood there. The setting was idyllic, and I was very happy, even if the place had shadows and some unsolicited happenings. It was my childhood sanctuary before awareness of that other, adult world closed in. More than half a century has passed by, the wheel of the years, the cycle of many seasons, so my childhood garden now seems like a far-off distant world - so far off that it may as well be in another galaxy a million light years away, or another universe of course. And yet... it still feels there. That's the strange thing. I know a little, what Dodgson meant, when he recollected moments that seemed to 'linger': liminal moments between adjacent worlds, hinted at along the surface of the ever-flowing stream. Flowing, flowing, on towards our own old age, our passing, and winter's breath scattering ice particles over, over the frosty grave. And yet... those 'golden hours', moments forever in their happening in time... they exist as much as we ever exist right now. They happen in their own place of time, that's all. And the 'autumn frosts' come of course. My cousin Menella died many years ago, and Alice Liddell: her sister Edith even sooner, dying at the age of 22, poor dear. Charles Dodgson too... all consigned now to a wonderland in time, as successive summers came and passed. But still - have you not known certain times in life yourself, when the moment or occasion seemed so 'now', so 'alive' that it still seems to tremble in its presence, like a sibilance on the breeze, a pulse of feeling like the stirring of spring, a mantra deep and low as a Tibetan horn in a monastic yard... shuddering your consciousness again, resonating onwards... and has the recollection of its vividness never left you? Clearly Charles Dodgson, recalling those golden moments in time along the river between Oxford and Godstow, and the dream-like reverie that seemed to befall them, sensed that though cut off in the years which followed, some kind of opening up had taken place (or some letting go)... an entry into dream world if you like... that was just - very, very present indeed... in the 'thisness' of its happening. This sense and awareness of entry into another world is not something to be worked out by the knowing, but by the unknowing... and yet it does seem that while we are still children we sometimes have a capacity to open up to wonder, that we all too often lose in the seriousness, control and closing down of adulthood. In many ways we become our own gatekeepers and the childhood spontaneity gets lost. Dodgson's own life and world was certainly constrained, by social propriety, class, doctrine, veneer. He himself upheld degrees of religious orthodoxy and in his Victorian society knew he must navigate, must negotiate social expectations and conformities. On the other hand, he also showed receptivity to more socially liberal minds, to imagination, and to the ease and spontaneity (I hesitate to say simplicity) of childhood... was drawn as well to those margin lands and other worlds explored by his friend George MacDonald... along the fringes between wonder and beguilement... all that otherness and presence that might almost break through into consciousness and encounter, at dusk in the fading light, in the shadowy woods, or along the ever-flowing stream... the quiet murmur of children, their chatter and openness, the sunlight coruscating along the surface of the waters. Children's capacity to be 'eager' and 'willing' to open to the imaginative realms (as recounted in the poem that opens 'A boat beneath a sunny sky') for Dodgson opened up the possibility of escape from the socially mundane, dull and controlled. They had imaginative openness that grown ups so often abandoned. The ability to wonder, to open up, to be receptive: the capacity for breakthrough into imaginative layers of consciousness. Children also perhaps had less pretence, enabling Dodgson himself to abandon a little pretence in their company, and simply delight in innocence, and a recovery of his own childhood innocence and fun. That, in my mind, was the attraction of children to Charles Dodgson. I say that as a relative, weary of the tired and jaded cynicism and the insinuations some people make. I can only pass on the family recollections of my aunts and grandmother: the way he would sit my aunts on his knee when they were children, and their fun and delight and positive memories of a kind old man (because by then he was old). Even in old age I suspect he saw children as a relief: as precious, as possessing openness and spontaneity, capable of inhabiting worlds that adults so often become cut off from, and which I believe Dodgson longed for all his life. (Even as a child himself he entertained his siblings.) Like Dodgson, the treasure of childhood has remained with me all my life. There are strange things in childhood, sometimes even terrors (Wonderland is not exactly a 'safe' place), but childhood also offers rhapsodic episodes of beauty and delight. The capacity to imagine makes a child so, so vulnerable, but also receptive as well. I form the impression that Alice Liddell was receptive and intelligent: responsive, engaged and direct. You see this capacity sometimes in gamers on the internet: the ability to be immersed, co-operating with imaginative storylines that unfold. Or again, why are so many of us - maybe you - attracted to films? That longing for imaginative immersion in an other world. Dodgson offers us that. The childhood world, because it veers beyond the controlled surface towards the imagination, and surrender to its narratives, exposes the child to a sometimes dream-like shambles of beauty, wonder, the grotesque, and even the terrifying. Other children's authors understood this: you see it in Roald Dahl, and even in a gentle story like Nina Bawden's 'Carrie's War' there is something adult and tense and frightening about Mr Evans, even as there is something safe and kindly about Hepzibah. In adult literature, a writer like Dickens opens his imagination wide to the grotesque... and we see that grotesquery in Alice too. Immersion removes safe controls and journeys beyond the safe and familiar. The garden I grew up in, which had also been Menella's childhood garden, often shimmered with beauty, and was a place of flourishing and freedom. But there was strangeness there too in that place and certain encounters I cannot explain to this day. If you are an imaginative child and you are open to an imaginative world, there are terrors and strangeness as well as childhood innocence, and those are represented in 'Alice's Adventures Under Ground'. It was just how it was in the childhood world I inhabited... full of wonder... before awareness started to become controlled and inhibited, and all the fear and closing down of adolescence and adulthood, and the pressures not to believe in the imaginative outskirts. Or are they outskirts? I kind of know myself through who I was in that garden, where I didn't have to pretend or defend. Later life takes courage, and courage can expand who we are, and we are not destined to remain children in sanctuary forever. Nevertheless I confess I still know myself there, and yearn for that garden and its beauty, and for me it's part of me, but a part I know I am cut off from, though I repeatedly try to reclaim myself there. As the words of the song say: 'We are stardust, we are golden, and we've got to get ourselves back to the garden.' I believe that Charles Dodgson, with the children and his stories and their adventures, was trying to get himself back into the garden. What should we make of it all? Of Dodgson and the children? Of Alice? And our own lives? Are we dreamed of, or do we dream? To turn to Shakespeare, are we "such stuff as dreams are made of?" Is one moment more existent than any other moment? Or is each moment strung along the thread of time, each one going on in its own present? In a billion years, or even in a few thousands, will we even be known, or will it be as if we never existed? And yet, now, our lives have the capacity to open to the glimmer and the gleam, the presence, the love and aliveness, the simple kindness. Here we are, drifting upon the stream of time, but this 'now' and our consciousness is our gift if we open up to it, and all the imagination and capacities we have within us. 'Life, what is it but a dream?' as Dodgson wrote. Well maybe, in effect, it is. But we are in it for this little while, whether we are dreaming or being dreamed about. Even if our lives were simulations of some greater intelligence (call it AI or call it God or universal consciousness... you decide), there is a capacity within us to open up to wonder and the imaginative life. It's an inheritance of childhood. To be sentient and sapient and feeling, beyond the terms and conditions of our own social captivity. (Sometimes we are the captors of ourselves, we police our own boundaries.) And yet what children sometimes teach us is something we may have partly lost: the capacity to let go and be, to be more open to things, and to be more expansive in what we dare to imagine and the journeys we dare to take. We don't know everything with certainty. Conceivably there really are other worlds and higher dimensions. At the frontiers of science we are sometimes led on by what we don't know, not by what we do know. The anomalies, the glitches in our understanding, the equations that should hold together but don't... they incite, they intrigue. But perhaps we should leave that to Borges and his 'Garden of Forking Paths'... or better still, in the best traditions of the old via negativa, we just let the words trail off....... Let's just leave Dodgson to thrill and delight the children, as the boat drifts on, and open up to the other world of Alice ourselves, going down and down into the dream and the adventures, our imagination opening, our wonder awakened once again.

|

|